I’ve been working on this paper since September, and I was hoping to publish it in a journal, but I learned today I’ve been scooped. So I see no harm now in publishing it here. I want to thank Frank Sayre and Charlie Goldsmith for their advice on it, which I clearly took too long to act on. I’m posting it as is for now but will probably refine it in the weeks to come.

Apologies to my regular readers for this extra-long and esoteric post.

Comments welcome!

***

Introduction

Reporting guidelines such as CONSORT,[1] PRISMA,[2] STARD,[3] and others on the EQUATOR Network [4] set out the minimum standards for what a biomedical research report must include to be usable. Each guideline has an associated checklist, and the implication is that every item in the checklist should appear in a paragraph or section of the final report text.

But what if, rather than a paragraph, each item could be a datum in a database?

Moving to a model of research reports as structured or semi-structured data would mean that, instead of writing reports as narrative prose, researchers could submit their research findings by answering an online questionnaire. Checklist items would be required fields, and incomplete reports would not be accepted by the journal’s system. For some items—such as participant inclusion and exclusion criteria—the data collection could be even more granular: each criterion, including sex, the lower and upper limits of the age range, medical condition, and so on, could be its own field. Once the journals receive a completed online form, they would simply generate a report of the fields in a specified order to create a paper suitable for peer review.

The benefits of structured reporting have long been acknowledged, Andrew’s proposal in 1994[5] for structured reporting of clinical trials formed the basis of the CONSORT guidelines. However, although in 2006 Wager did suggest electronic templates for reports and urged researchers to openly share their research results as datasets,[6] to date neither researchers nor publishers have made the leap to structuring the components of a research article as data.

Structured data reporting is already becoming a reality for practitioners: radiologists, for example, have explored the best practices for structured reporting, including using a standardized lexicon for easy translation.[7] A study involving a focus group of radiologists discussing structured reporting versus free text found that the practitioners were open to the idea of reporting templates as long as they could be involved in their development.[8] They also wanted to retain expressive power and the ability to personalize their reports, suggesting that a hybrid model of structured and unstructured reporting may work best. In other scientific fields, including chemistry, researchers are recognizing the advantage of structured reporting to share models and data and have proposed possible formats for these “datuments.”[9] The biomedical research community is in an excellent position to learn from these studies to develop its own structured data reporting system.

Reports as structured data, submitted through a user-friendly, flexible interface, coupled with a robust database, could solve or mitigate many of the problems threatening the efficiency and interoperability of the existing research publication system.

Problems with biomedical research reporting and benefits of a structured data alternative

Non-compliance with reporting guidelines

Although reporting guidelines do improve the quality of research reports,[10],[11] Glasziou et al. maintain that they “remain much less adhered to than they should be”[12] and recommend that journal reviewers and editors actively enforce the guidelines. Many researchers may still not be aware that these guidelines exist, a situation that motivated the 2013 work of Christensen et al. to promote them among rheumatology researchers.[13] Research reports as online forms based on the reporting guidelines would raise awareness of reporting guidelines and reduce the need for human enforcement: a report missing any required fields would not be accepted by the system.

Inefficiency of systematic reviews

As the PRISMA flowchart attests, performing a systematic review is a painstaking, multi-step process that involves scouring the research literature for records that may be relevant, sorting through those records to select articles, then reading and selecting among those articles for studies that meet the criteria of the topic being reviewed before data analysis can even begin. Often researchers isolate records based on eligibility criteria and intervention. If that information were stored as discrete data rather than buried in a narrative paragraph, relevant articles could be isolated much more efficiently. Such a system would also facilitate other types of literature reviews, including rapid reviews.[14]

What’s more, the richness of the data would open up avenues of additional research. For example, a researcher interested in studying the effectiveness of recruitment techniques in pediatric trials could easily isolate a search to the age and size of the study population, and recruitment methods.

Poorly written text

Glasziou et al. point to poorly written text as one of the reasons a biomedical research report may become unusable. Although certain parts of the report—the abstract, for instance, and the discussion—should always be prose, information design research has long challenged the primacy of the narrative paragraph as the optimal way to convey certain types of information.[15],[16],[17] Data such as inclusion and exclusion criteria are best presented as a table; a procedure, such as a method or protocol, would be easiest for readers to follow as a numbered list of discrete steps. Asking researchers to enter much of that information as structured data would minimize the amount of prose they would have to write (and that editors would have to read), and the presentation of that information as blocks of lists or tables would in fact accelerate information retrieval and comprehension.

Growth of journals in languages other than English

According to Chan et al.,[18] more than 2,500 biomedical journals are published in Chinese. The growth of these and other publications in languages other than English means that systematic reviews done using English-language articles alone will not capture the full story.[19] Reports that use structured data will be easier to translate: not only will the text itself—and thus its translation—be kept to a minimum, but, assuming journals in other languages adopt the same reporting guidelines and database structure, the data fields can easily be mapped between them, improving interoperability between languages. Further interoperability would be possible if the questionnaires restricted users to controlled vocabularies, such as the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) and the International Classification of Health Interventions (ICHI) being developed.

Resistance to change among publishers and researchers

Smith noted in 2004 that the scientific article has barely changed in the past five decades.[20] Two years later Wager called on the research community to embrace the opportunity that technology offered and publish results on publicly funded websites, effectively transforming the role of for-profit publishers to one of “producing lively and informative reviews and critiques of the latest findings” or “providing information and interpretation for different audiences.” Almost a decade after Wager’s proposals, journals are still the de facto publishers of primary reports, and, without a momentous shift in the academic reward system, that scenario is unlikely to change.

Moving to structured data reporting would change the interface between researchers and journals, as well as the journal’s archival infrastructure, but it wouldn’t alter the fundamental role of journals as gatekeepers and arbiters of research quality; they would still mediate the article selection and peer review processes and provide important context and forums for discussion.

The ubiquity of online forms may help researchers overcome their reluctance to adapt to a new, structured system of research reporting. Many national funding agencies now require grant applications to be submitted online,[21],[22] and researchers will become familiar with the interface and process.

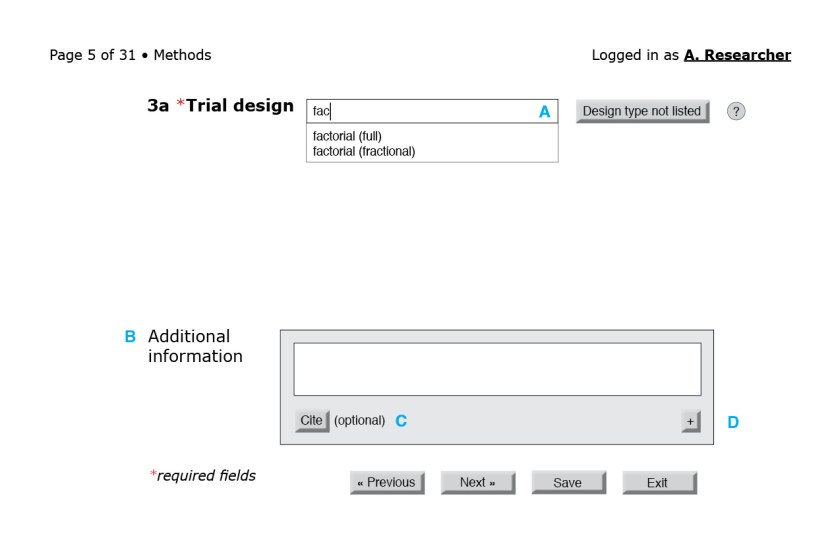

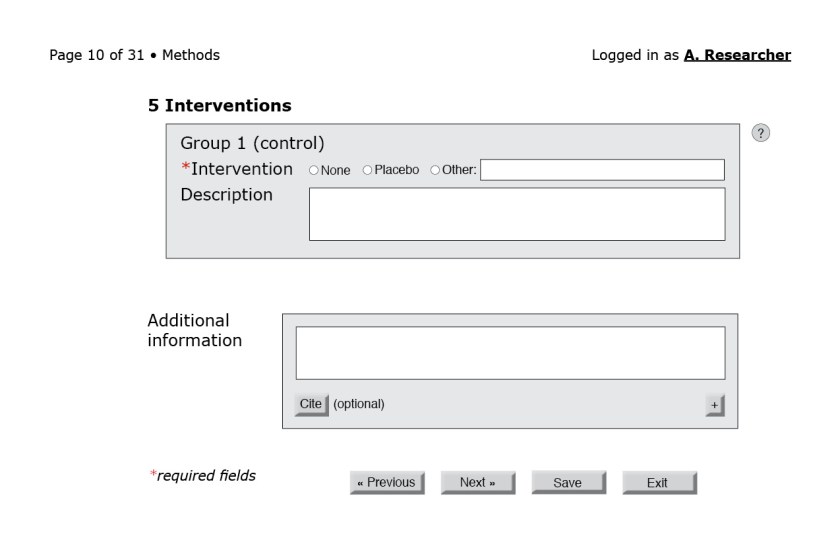

A model interface

To offer a sense of how a reporting questionnaire might look, I present mock-ups of select portions of a form for a randomized trial. I do not submit that they are the only—or even the best—way to gather reporting details from researchers; these minimalist mock-ups are merely the first step toward a proof of concept. The final design would have to be developed and tested in consultation with users.

In the figures that follow the blue letters are labels for annotations and would not appear on the interface.

![Figure 3: First page of the CONSORT questionnaire. (A) Because reporting guidelines and checklists vary in length, only after the form loads can the interface indicate progress through the questionnaire. A user-friendly system would also include a way for users to jump to a specific question or page. (B) The help button to the right of each field could bring up the associated section of the CONSORT Explanation and Elaboration document. (C) An autocomplete field with a controlled vocabulary of the possible sections in a structured abstract, such as the one from the National Library of Medicine.[23] (D) Required fields are indicated by an asterisk. (E) Users should be able to navigate to the next page without filling required fields in this particular page. Only at the end of the questionnaire will the system flag empty required fields. (F) Users should be able to save their progress at any time. Better yet, the system could autosave at regular intervals. (G) Users should also be able to exit at any point.](https://i0.wp.com/ivacheung.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/QuestionnaireInterface-3.jpg?resize=840%2C544&ssl=1)

Other considerations

Archives

When journals moved from print to online dissemination, publishers recognized the value of digitizing their archives so that older articles could also be searched and accessed. Analogously, if publishers not only accepted new articles as structured data but also committed to converting their archives, the benefits would be enormous. First, achieving the eventual goal of completely converting all existing biomedical articles would help researchers perform accelerated systematic reviews on a comprehensive set of data. Second, the conversion process would favour published articles that already comply with the reporting guidelines; after conversion, researchers would be able to search a curated dataset of high-quality articles.

I recognize that the resources needed for this conversion would be considerable, and I see the development of a new class of professionals trained in assessing and converting existing articles. For articles that meet almost but not quite all reporting guidelines, particularly more recent publications, these professionals may succeed in acquiring missing data from some authors.[24] Advances in automating the systematic review process[25] may also help expedite conversion.

Software development for the database and interface

In “Reducing waste from incomplete or unusable reports of biomedical research,” Glasziou et al. call on the international community to find ways to decrease the time and financial burden of systematic reviews and urge funders to take responsibility for developing infrastructure that would improve reporting and archiving. To ensure interoperability and encourage widespread adoption of health reports as structured data, I urge the international biomedical research community to develop and agree to a common set of standards for the report databases, in analogy to the effort to create standards for trial registration that culminated in the World Health Organization’s International Standards for Clinical Trial Registries.[26] An international consortium dedicated to developing a robust database and flexible interface to accommodate reporting structured data would also be more likely to secure the necessary license to use a copyrighted controlled vocabulary such as the ICD.

Implementation

Any new system with wide-ranging effects must be developed in consultation with a representative sample of users and adquately piloted. The users of the report submission interface will largely be researchers, but the report generated by the journal could be consulted by a diverse group of stakeholders—not only researchers but also clinicians, patient groups, advocacy groups, and policy makers, among others. A parallel critical review of the format of this report would provide an opportunity to assess how best to reach audiences that are vested in discovering new research.

Although reporting guidelines exist for many different types of reports can each serve as the basis of a questionnaire, I recommend a review of all existing biomedical reporting guidelines together to harmonize them as much as possible before a database for reports is designed, perhaps in collaboration with the BioSharing initiative[27] and in an effort similar to the MIBBI Foundry project to “synthesize reporting guidelines from various communities into a suite of orthogonal standards” in the biological sciences.[28] For example, whereas recruitment methods are required according to the STARD guidelines, they are not in CONSORT. Ensuring that all guidelines have similar basic requirements would ensure better interoperability among article types and more homogeneity in the richness of the data.

Conclusions

Structuring biomedical research reports as data will improve report quality, decrease the time and effort it takes to perform systematic reviews, and facilitate translations and interoperability with existing data-driven sysetms in health care. The technology exists to realize this shift, and we, like Glazsiou et al., urge funders and publishers to collaborate on the development, in consultation with users, of a robust reporting database system and flexible interface. The next logical step for research in this area would be to build a prototype and for researchers to use while running a usability study.

Reports as structured data aren’t a mere luxury—they’re an imperative; without them, biomedical research is unlikely to become well integrated into existing health informatics infrastructure clinicians use to make decisions about their practice and about patient care.

Sources

[1] “CONSORT Statement,” accessed October 04, 2014, http://www.consort-statement.org/.

[2] “PRISMA Statement,” accessed October 04, 2014, http://www.prisma-statement.org/index.htm.

[3] “STARD Statement,” n.d., http://www.stard-statement.org/.

[4] “The EQUATOR Network | Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of Health Research,” accessed September 26, 2014, http://www.equator-network.org/.

[5] Erik Andrew, “A Proposal for Structured Reporting of Randomized Controlled Trials,” JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association 272, no. 24 (December 28, 1994): 1926, doi:10.1001/jama.1994.03520240054041.

[6] Elizabeth Wager, “Publishing Clinical Trial Results: The Future Beckons.,” PLoS Clinical Trials 1, no. 6 (January 27, 2006): e31, doi:10.1371/journal.pctr.0010031.

[7] Roberto Stramare et al., “Structured Reporting Using a Shared Indexed Multilingual Radiology Lexicon.,” International Journal of Computer Assisted Radiology and Surgery 7, no. 4 (July 2012): 621–33, doi:10.1007/s11548-011-0663-4.

[8] J M L Bosmans et al., “Structured Reporting: If, Why, When, How-and at What Expense? Results of a Focus Group Meeting of Radiology Professionals from Eight Countries.,” Insights into Imaging 3, no. 3 (June 2012): 295–302, doi:10.1007/s13244-012-0148-1.

[9] Henry S Rzepa, “Chemical Datuments as Scientific Enablers.,” Journal of Cheminformatics 5, no. 1 (January 2013): 6, doi:10.1186/1758-2946-5-6.

[10] Robert L Kane, Jye Wang, and Judith Garrard, “Reporting in Randomized Clinical Trials Improved after Adoption of the CONSORT Statement.,” Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 60, no. 3 (March 2007): 241–49, doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.06.016.

[11] N Smidt et al., “The Quality of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies since the STARD Statement: Has It Improved?,” Neurology 67, no. 5 (September 12, 2006): 792–97, doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000238386.41398.30.

[12] Paul Glasziou et al., “Reducing Waste from Incomplete or Unusable Reports of Biomedical Research.,” Lancet 383, no. 9913 (January 18, 2014): 267–76, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62228-X.

[13] Robin Christensen, Henning Bliddal, and Marius Henriksen, “Enhancing the Reporting and Transparency of Rheumatology Research: A Guide to Reporting Guidelines.,” Arthritis Research & Therapy 15, no. 1 (January 2013): 109, doi:10.1186/ar4145.

[14] Sara Khangura et al., “Evidence Summaries: The Evolution of a Rapid Review Approach.,” Systematic Reviews 1, no. 1 (January 10, 2012): 10, doi:10.1186/2046-4053-1-10.

[15] Patricia Wright and Fraser Reid, “Written Information: Some Alternatives to Prose for Expressing the Outcomes of Complex Contingencies.,” Journal of Applied Psychology 57, no. 2 (1973).

[16] Karen A. Schriver, Dynamics in Document Design: Creating Text for Readers (New York: Wiley, 1997).

[17] Robert E. Horn, Mapping Hypertext: The Analysis, Organization, and Display of Knowledge for the Next Generation of On-Line Text and Graphics (Lexington Institute, 1989).

[18] An-Wen Chan et al., “Increasing Value and Reducing Waste: Addressing Inaccessible Research.,” Lancet 383, no. 9913 (January 18, 2014): 257–66, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62296-5.

[19] Andra Morrison et al., “The Effect of English-Language Restriction on Systematic Review-Based Meta-Analyses: A Systematic Review of Empirical Studies.,” International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care 28, no. 2 (April 2012): 138–44, doi:10.1017/S0266462312000086.

[20] R. Smith, “Scientific Articles Have Hardly Changed in 50 Years,” BMJ 328, no. 7455 (June 26, 2004): 1533–1533, doi:10.1136/bmj.328.7455.1533.

[21] Australian Research Council, “Grant Application Management System (GAMS) Information” (corporateName=The Australian Research Council; jurisdiction=Commonwealth of Australia), accessed October 04, 2014, http://www.arc.gov.au/applicants/rms_info.htm.

[22] Canadian Institutes for Health Research, “Acceptable Application Formats and Attachments—CIHR,” November 10, 2005, http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/29300.html.

[23] “Structured Abstracts in MEDLINE®,” accessed January 14, 2015, http://structuredabstracts.nlm.nih.gov/.

[24] Shelley S Selph, Alexander D Ginsburg, and Roger Chou, “Impact of Contacting Study Authors to Obtain Additional Data for Systematic Reviews: Diagnostic Accuracy Studies for Hepatic Fibrosis.,” Systematic Reviews 3, no. 1 (September 19, 2014): 107, doi:10.1186/2046-4053-3-107.

[25] Guy Tsafnat et al., “Systematic Review Automation Technologies.,” Systematic Reviews 3, no. 1 (January 09, 2014): 74, doi:10.1186/2046-4053-3-74.

[26] World Health Organization, International Standards for Clinical Trial Registries (Genevia, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2012), www.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/76705/1/9789241504294_eng.pdf.

[27] “BioSharing,” accessed October 12, 2014, http://www.biosharing.org/.

[28] “MIBBI: Minimum Information for Biological and Biomedical Investigations,” accessed October 12, 2014, http://mibbi.sourceforge.net/portal.shtml.